The Invisible Hours review: a new modality for immersive theatre

The Invisible Hours is a narrative-driven experience that combines aspects of a movie, video game and immersive theatre production. However the developers at Tequila Works couldn’t be clearer about how they intend the work to be classified, through text displayed during a load screen declaring: “This is not a game. This is not a movie. This is a piece of immersive theatre with many tangled threads.” Presumably these “tangled threads” are a reference to its knotty array of backstories, involving a handful of characters, each a suspect in a good ol’ fashioned murder mystery that unfolds in an opulent mansion circa the late 1800s.

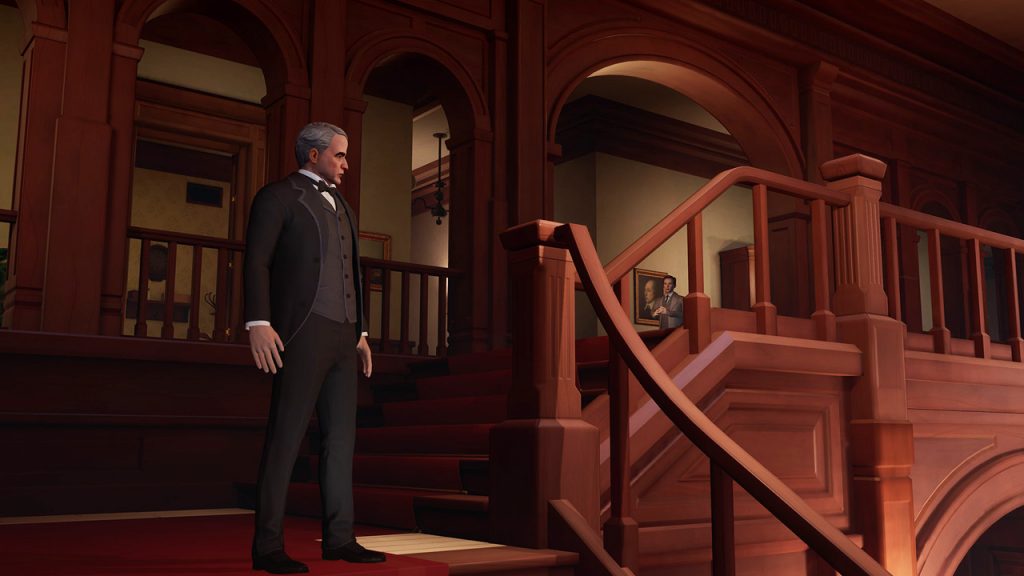

The mansion is owned by none other than Nikola Tesla (voiced by Uriel Emil), who is also the victim, his body still warm when the story begins. A rather huffy and confrontational Thomas Edison (Mark Arnold) is one of the suspects; the others are Tesla’s butler, his former assistant, a famous actor, the son of a railroad tycoon, and a rough-as-guts cockney goon, who we assume isn’t guilty because it’d be too bloody obvious. Everybody—as these things tend to go—harbors secrets, gradually revealed over the runtime, which lasts for a few hours depending on how you choose to experience it (more on that in a moment).

Release date, October 10, 2017

Available on: Oculus Rift, Steam, PSVR

PSVR2

Experienced on: Oculus Rift, PSVR

There are two detectives. One is a character within the narrative universe: Gustaf Gustav (Henning Valin Jakobsen), a Swede who drinks heavily and grows increasingly frustrated by everybody’s antics, demonstrating that—quelle surprise!—boozing and sleuthing might not be an ideal combination. The other is us. Our job is to snoop around in ways Gustav cannot, essentially as an embodied camera or omnipotent onlooker. The phrase “fly on the wall”—which of course refers to undetected eavesdropping—is often used in relation to film documentaries, but it makes more sense here, where we can indeed buzz around incognito.

The Invisible Hours’ official plot description states that “the player is invisible, with freedom to follow and observe anyone in the story.” But if our role is almost entirely to watch (though we also have the ability to pick up and inspect some objects) should we really be described as a “player”? That seems like an odd label to use given the aforementioned insistence that we’re not playing a video game. Perhaps the developers at Tequila Works couldn’t stomach using the term “audience,” with its inferences of passivity and a one-way, teller-listener paradigm.

The crucial feature that The Invisible Hours contains, which traditional immersive theatre productions do not, is the ability to control the flow of time—an addition that solves some key challenges. The biggest one is how to communicate a coherent narrative while enabling—perhaps also encouraging—exploration. During my first (real world) immersive theatre production I was easily distracted, venturing through various rooms and spaces, leading to a narratively fractured experience. During my second I took a radically different approach, selecting one actor and—trying not to feel like a stalker—following them around for the entire runtime, resulting in a smooth story arc but a limited overview of the drama.

The structure of the third immersive theatre production I attended did some of this work for me. It was split into three 30 minute parts, which I might otherwise have called “acts,” were they not the same scenes unfolding in the same ways. The second and third parts jumped back in time, rewinding the experience to the beginning, allowing audience members to catch up on moments they missed and thus form a full or full-ish picture of the drama.

The ability to pause, fast forward or rewind at any time in The Invisible Hours means, with a bit of fidgeting around, you can absorb every scene any number of times. At the time of publishing this review (more than six years after its release) there aren’t many VR experiences like it, which is another way of saying this approach hasn’t caught on. One notable exception is a section of the surreal and innovative The Under Presents titled “The Timeboat,” which similarly casts the viewer as an omnipotent observer, investigating strange goings-on during an ill-fated scientific voyage to the arctic. An additional feature in Timeboat is the ability to switch to a third person, diorama-esque perspective, zooming out of the ship to observe it from high above.

The easiest, and probably most effective path through The Invisible Hours is to select a character, which the experience then automatically follows for you, even deciding the virtual camera angles. After completing each chapter (there are four) you can then select a different character, rewind, and watch all that person’s scenes, then repeat the process again, moving through the cast. But this methodological approach isn’t the most fun. It also requires you to hold your ground when the experience tugs at you to go somewhere else—for instance when, during a conversation or moment of solitude, you hear raised voices from another room, as if the developers are whispering “go check it out…you know you want to…”

Given the spine of the experience is dialogue exchanges, the pressure was on for the writing and direction to have colour and flair. But many scenes lack spark, however, and feel a little flat. But they’re always pretty good—good enough to keep you engaged, notwithstanding an ever-present itch to go elsewhere or fast-forward. The latter is an example of what happens when you add a novel new modality: one feels inclined to use it, even when doing so might not lead to the most satisfying experience.

This is what you get with experimental, perhaps even pioneering productions. There isn’t an established set of codes and conventions; no agreed upon principles for satisfying drama. Which makes the space exciting and precarious.