SENS review: oddly fusing game, film and graphic novel

Released in 2016, SENS VR arrived during a period of intensive experimentation, when VR content creators threw all sorts of stuff at the wall to see what stuck. Written by Charles Ayats, Armand Lemarchand and Marc-Antoine Mathieu, the experience was billed as “the first virtual reality game inspired by a graphic novel,” and one in which “you play a man lost in a maze of strange laws.” Its interactive elements have broadly the same level of complexity as those in Notes on Blindness and The Turning Forest (two other early titles, released around the same time), predominantly concerned with prompting the progression of various sequences, not so much played as activated.

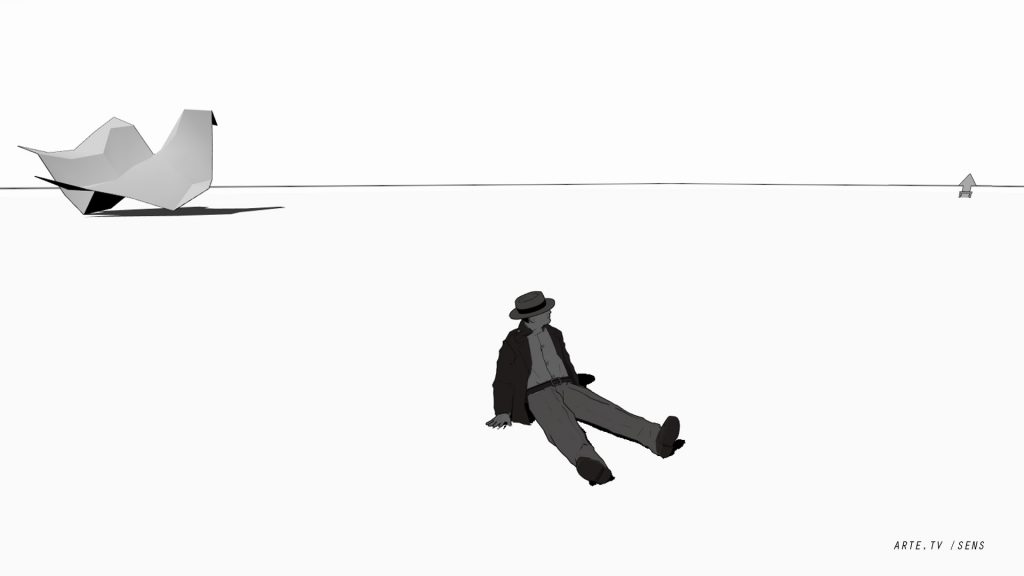

It begins in darkness, a crack of light appearing before us as we’re being pushed forward towards it. Eventually the shape of a door is revealed. Once we press a button, when our gaze is directed at the handle, the handle turns, the door opens and the immersion pushes forward, into a stark and sparse white landscape—an aesthetic resembling a monochrome graphic novel.

Developer: Red Corner

Year of release: 2016

Available on: Samsung Gear VR, Oculus Rift, Quest headsets

Experienced on: Samsung Gear VR

SENS unfolds from a first-person perspective, the shadow of the character we’ve embodied projected onto the ground—a noir-like figure of a man wearing a trenchcoat and an akubra hat. We have no ability to control which direction we move beyond the most simplistic and predetermined “point and click” approach. Soon we arrive at a signpost with a series of signs stuck to it pointing in multiple directions.

We naturally assume that clicking on a certain arrow takes us in the direction the arrow is pointed, allowing a rudimentary form of navigation. Instead, each time a sign is clicked it falls off the pole; when every sign has fallen, a shadow on the ground remains, showing an arrow pointing diagonally to the right.

The sight of signs, pointing in various directions, inferring we have the liberty of controlling our own course of action, has been a ruse; we never had a choice. This moment crystalises the frustrating sensation of existing in an environment that beckons to be explored, only for us to be pushed through a dictatorial experience in which we’re guided from one point to the next, unable to depart the beaten track.

Chapter one (there are three) concludes in third person perspective, showing our noirish, gumshoe-like character riding a giant arrow as if it were a magic carpet, over dozens of block-like edifices in the shape of huge arrows, pointing in every conceivable direction. This is the image from SENS that stays with me. Arrows are its core visual motif, as well a frustrating source of irony, imparting a sense of explorative freedom we’re never afforded.

There are flashes of other kinds of interactivity leading to moments of visual aplomb (such as the ability to control shadows on the ground by moving one’s head leftwards and rightwards) but the experience is hampered throughout by its obvious limitations. To best appreciate SENS, don’t think about interactive elements at all. Or consider them the equivalent of turning a page in a book—which speaks to the experience’s legacy as a strange fusion of game, film, and graphic novel.