Notes on Blindness review: differently perceiving perception

Notes on Blindness was conceived as an immersive companion piece to the 2016 film of the same name, which explores the process of going blind from the very personal perspective of theology professor John Hull. The late scholar’s extensive audiotape recordings, full of poignant observations, form the spine of both experiences, which take different forms and approaches. Don’t go into the 25 minute-ish VR production expecting directors Arnaud Colinart, Amaury La Burthe, Peter Middleton and James Spinney to graft the grammar and syntax of traditional filmmaking onto virtual reality, and hope for the best, as many others have.

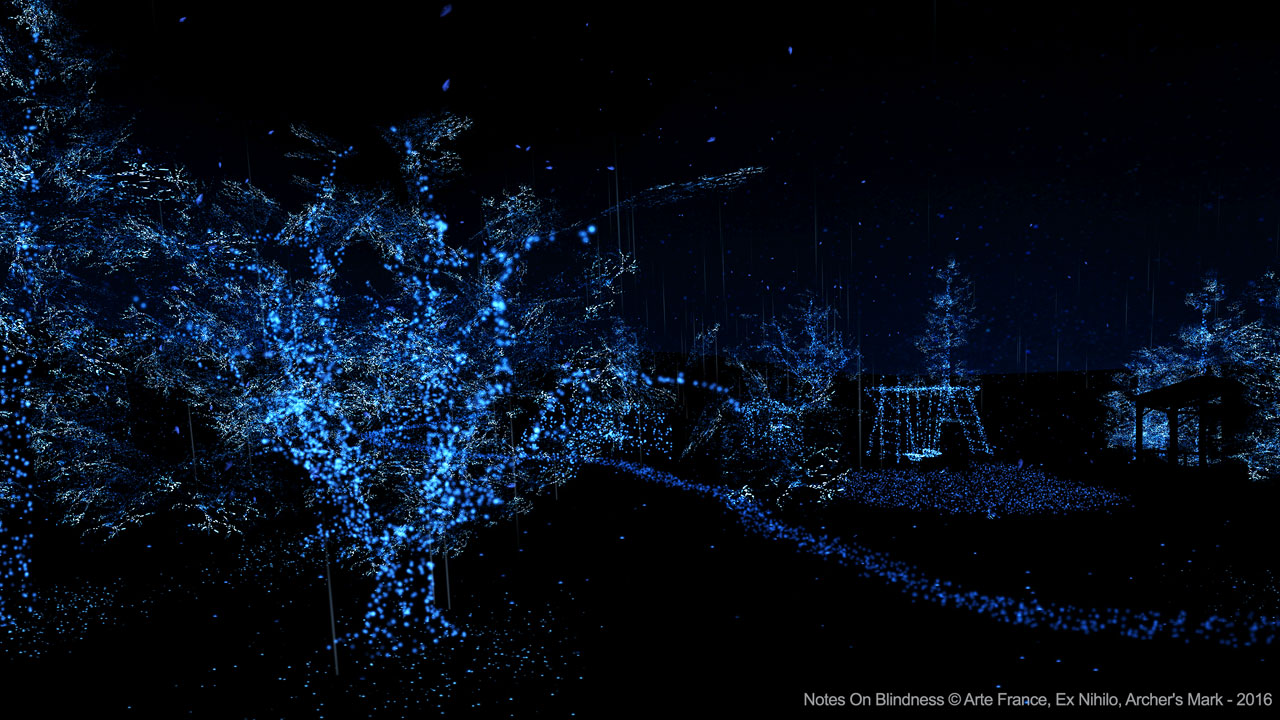

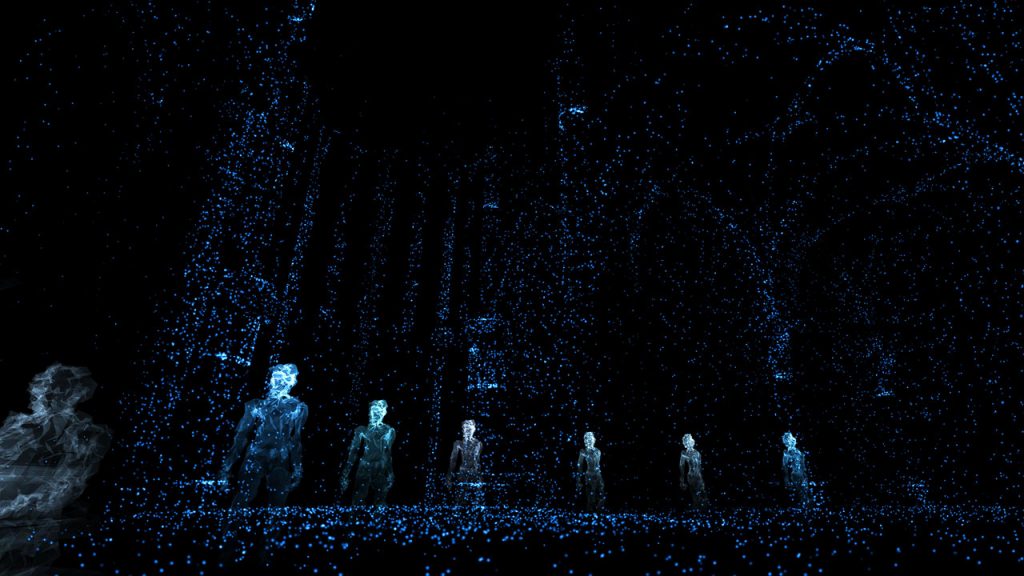

Nothing could be further from the truth: every scene, every immersion in this exquisitely humane experience reflects an understanding that VR requires new forms of storytelling—and those forms involve using space to reveal information. In the first of a handful of environments, each textured with a surreal pixelated aesthetic, we’re positioned in a public park, with Hull commenting on the sounds of things around him. There are footsteps of women in high-heeled shoes; the rustling of a newspaper from a person sitting on a bench; the sounds of cars stopping and starting in the carpark.

Year of release: 2016

Available on: Oculus Rift, Quest headsets

PSVR2

Experienced on: Oculus Rift, Meta Quest 2

These events correspond with their visual and aural emergence in the darkened tableau around us. It’s a simple process: we hear them, then turn and look. But it’s executed with an elegance and thoughtfulness that imbues prosaic occurences with profound qualities.

“It’s a world that consists only of activity,” Hull reflects, early in the piece. “Where there’s activity there’s no sound, and that’s where part of the world dies.” When he finishes that last sentence, the audio goes quiet and the visuals vanish, marking the end of the first chapter. Each take the interactive elements in slightly different directions, chapter two for instance enabling us to create wind and “reveal the scene.” We shoot bursts of virtual breezes that mix with particular elements, like a swing and wind chimes, and visually awaken them.

My favourite moment takes place in the third chapter, which is situated inside, Hull reflecting on rain and how he became “lost in the beauty of it.” Rainfall, he says, brings out the sounds of things; he longs for “something equivalent to rain falling inside.” This imaginative pondering is actualised: we can look at objects, again painted with that lovely blue pixelation, to create rain that brings them into focus. This part of Hull’s reflections, which embody his delicate turn of phrase (“cognition is beautiful…it’s beautiful to know”), was also used to lovely effect in the feature film. Hull’s tapes, his notes on blindness, were a great find, exploited in both productions for their deeply ruminative qualities.

It’d be folly to approach Notes on Blindness believing it could in any way replicate the experience of going blind—which is impossible and beside the point. A far greater prerogative for the directors was making the case that familiar occurrences—as simple as people walking or singing, and water falling from the sky—can be profoundly special depending on perception and perspective. Notes on Blindness is about experiencing the world differently, contemplating things differently, perceiving perception itself differently. Hull’s ultimate conclusion, like the production itself, is simple but profound: “being human is not seeing; it’s loving.”