Metallica on Apple Vision Pro review: energetic but cookie-cut

I wasn’t surprised, while watching the new Metallica immersive video, to find myself in the personal space of the band as they perform for a stadium crowd in Mexico CIty. In this medium, one hopes for and expects intimate encounters. What did catch me off-guard was being pushed so regularly and so intensely into the space of the band’s loud and extremely sweaty fans—their eyes wild and mouths agape, like possessed rodeo clowns.

The cameras move so dramatically towards these people I swear I was privy to extreme halitosis—although, admittedly, the Apple Vision Pro headset I watched this on did not come with any odor-based innovation. If the experience could drift up our nostrils, I imagine it smelling like unwashed clothes, tacos, beer and bong water.

Release date: March 14, 2025

Available on: Apple Vision Pro

Experienced on: Apple Vision Pro

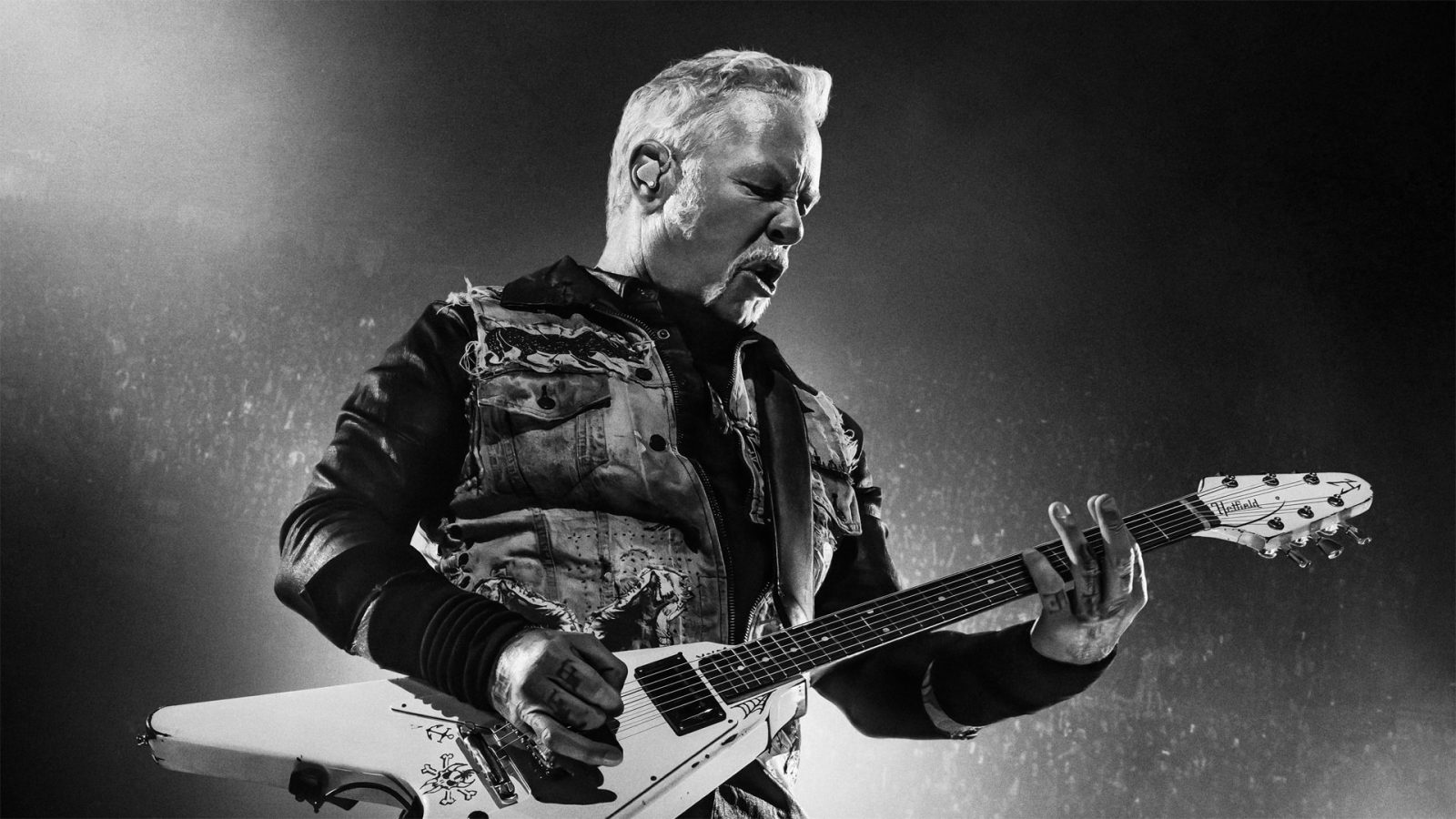

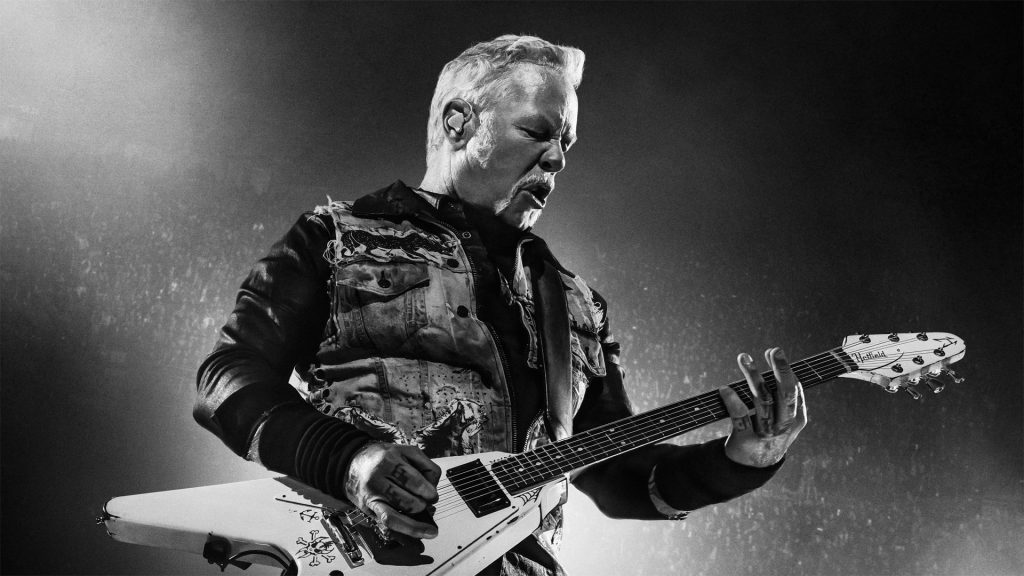

Running for 25 minutes, the production vividly captures the excitement of a stadium; the roar of the crowd. It hones in on individual faces because, without their vein-bulging visages, the audience is just a sea of ants. It also of course incorporates the band members: singer James Hetfield, drummer Lars Ulrich, guitarist Kirk Hammett, and bassist Robert Trujillo. Each gets a crisp monochrome profile shot and a slab of voice-over ruminating on their work and rock pig ethos. They perform three iconic tracks: Whiplash, One, and Enter Sandman.

Whoever put this video together (I can’t find any production details, and it contains no credits) clearly understands how to make a slick concert video, squeezing lots of juice from the pulp. Shots are handsomely sculpted, using an elaborate rig of cameras, and there are some visually interesting embellishments, including a transition from smokey monochrome to full-blown colour—which brought to mind a psychedelic flower blooming in fast-forward. But understanding filmmaking language isn’t the same as delivering a great spatial computing experience.

This production is fine if you’re after a familiar format, zhuzhed up with some extra bells and whistles, but the future of spatial entertainment it most certainly is not, despite the inevitable froth from VR enthusiasts who once again leave no hyperbolic stone unturned. Take, for instance, the following sentences in this review, which landed on my palate like a shot of vinegar: “The video is 25 minutes long and represents a landmark moment in the history of virtual reality. Some Metallica fans will walk into Apple Stores, hear Whiplash during a demo, and then make a $3500 purchase to experience One and Enter Sandman at home too.”

How many times have you read words like that—a “landmark moment in the history of virtual reality?” Ivan Sutherland’s “The Sword of Damocles” was a landmark. The Oculus Rift DK1 was a landmark. James Hetfield rocking out, within spitting distance of the camera, was…not a landmark. As for the second sentence: really? A Metallica fan will pay US$3500 to own a device simply to access a 25 minute video, when they could watch entire concerts on the teev for a few bucks? This is crazy talk, feeding into the myth of the “killer app,” which don’t really exist—at least not in terms of widespread uptake of a device that costs thousands of dollars.

Back to my previous point: the Metallica immersive video is quite well made and a decent demonstration of some of the Vision Pro’s specs, i.e. crispness and resolution. But it’s not an indication of where the amazing universe of spatial computing is heading. Every new medium begins by mimicking the language of the old, a process observable through content as well as the nomenclature used to describe it (early films for instance were called “photoplays”).

Almost all 180 videos are bedded to the language of motion pictures, being non-interactive sculpted experiences presented on screen-like spaces. Some embrace a more immersive, embodied-camera style, such as Robert Rodriguez’s impressive THE LIMIT. Another Vision Pro title, Who is Sabato De Sarno? A Gucci Story, proposes a curious middle ground, displaying a flat screen presentation but utilising the space between screen and spectator. When the subject is shown boarding a tram, for example, a virtual rendering of that vehicle is summoned into our own real world environment.

Imagine an immersive Metallica experience in which you can choose which band member to follow, or move through the space yourself, or use your fingers to alter perspective—zooming right up to Hetfield’s nostril hair, or way out, until the musicians become the size of LEGO figures. The possibilities are endless. Reheating a cookie-cut format provides, in this case, a perfectly fine viewing experience, with banging tunes and zeal. But it’s far from innovative.