Maestro review: a well-established rhythm format

One YouTube reviewer declared that Maestro “nails the feeling of being a conductor.” I’d pay good money to be in the company of an actual conductor as they listen to those words: I imagine they’d react viscerally, like a sommelier quaffing two buck chuck. The developers want players to feel like a baton-wielding virtuoso, sure, but only a fool would believe this as an accurate depiction of the profession. The game is boosted by the fact that almost nobody knows what a conductor really does or how they do it; it looks like just a lot of arm waving and air stabbing.

The core challenge isn’t to offer a realistic simulation, but to take the end result—the visual performance—and retrospectively fit it to satisfying gameplay mechanics. This process makes the music subservient to the visuals, even though it feels like the other way around.

Developer: Double Jack

Release date: October 17, 2024

Available on: Quest headsets, Steam VR

Experienced on: Meta Quest 3

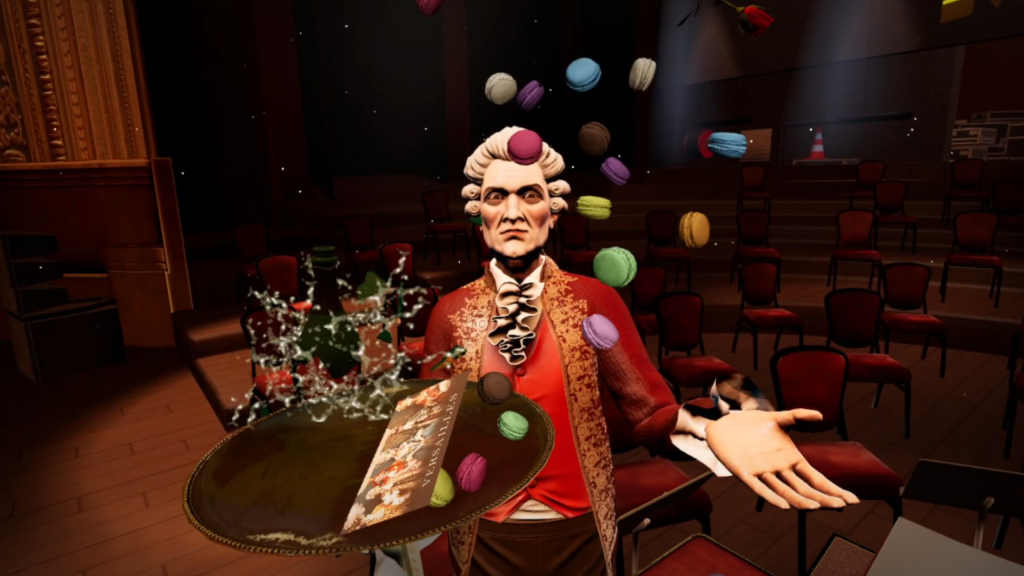

As in countless rhythm games, shapes appear to indicate what actions need to be performed and when we need to perform them. The direction of arrows rolling towards us shows which direction to swipe our hands (we must do this when they cross over a horizontal line) and circles appear around the tableau indicating where to point to activate particular parts of the orchestra. Different coloured ramp-like streaks of light reveal whether we need to lift or drop our left hand: yellow to raise it, blue to lower. The music we conduct is a roll call of classical bangers, from Carmina Burana to Swan Lake and Ride of The Valkyries.

The well-established rhythm gaming format, which emphasises timing over graphical prowess, hasn’t developed much conceptually speaking over the decades. Maestro exploits hand tracking technology, which at the time of publishing is still a relatively new headset feature, meaning you can ditch your controllers and cut loose with your own body, which is unquestionably liberating. But even this is hardly a new feature: the pioneering 90s arcade game Dance Dance Revolution also brought the whole body into it, rolling out a “stage” with stompable footpads, displaying arrows that correspond to on-screen instructions.

While VR games such as Walkabout Mini Golf and Eleven Table Tennis feature physics-based mechanics that clearly benefit from the corporeal nature of headset experiences, in Maestro what’s old again is new again—returning those arrows, rejigging the Dance Dance formula. Which is not to say I didn’t have fun: it’s an enjoyable game, best and perhaps inevitably played in short bursts. It’s hard to imagine doing this for an entire afternoon—or even a couple of hours. The experience belongs to a canon that currently comprises the bulk of VR gaming experiences: short, gimmicky content that’s perfectly fine for 20 minutes but can be easily put aside and forgotten about.

This kind of content is comparable to the (mostly forgotten) films that filled the earliest years of motion pictures, famously described by scholar Tom Gunning as “The Cinema of Attractions,” referencing their ride-like appeal. Ideally, rather than forming singular experiences, games like Maestro (the sword-fighting simulator Blade & Sorcery also comes to mind) would be absorbed into much larger productions that offer more to do, more branches to hold onto.

This has already started to happen. The developers of the AAA VR game Horizon Call of the Mountain would surely have learnt a thing or two from The Climb, a gimmicky experience, like Maestro, dedicated to executing a single concept; no prizes for guessing what that is. In effect they delivered, with Call of the Mountain, their own climbing simulator, at blockbuster scale—with lots of bells and whistles, additional exploration and combat elements, an overarching narrative, and big juicy set pieces.

I can imagine Maestro forming a memorable part of an Assassin’s Creed game: perhaps, in one chapter, we’re required to impersonate a conductor in order to kill a royal dignitary using a dagger disguised as a baton. I liked “conducting” Carmina Burana; I might’ve enjoyed it more had I ended my performance by murdering somebody in the front row, then escaping via grappling hook.