Lovesick review: a scuzzy narrative puzzler with maddening mechanics

In the not-too-distant future, when virtual reality’s embryonic years have become a dim memory, VR enthusiasts such as myself will recall certain things with a nostalgic twinkle in our eyes. For others, we’ll think “thank God we don’t have to put up with that anymore.” An example of the latter will be node-based navigation systems, whereby, instead of being about to move around environments freely, players must choose between predetermined waypoints—areas of the tableau the developers have deemed accessible.

A rare example of a VR production that deploys this system in interesting ways is the 2017 horror production Wilson’s Heart, in which we embody a patient trapped inside an old and creaky asylum. While still stifling, its node-based navigation has a curious effect on pacing and the divulging of spatial information. As I wrote in my review: “Every relocation via node is a new tableau, a new mini-scene, an opportunity for surprises and reveals.”

Developer: Rose City Games

Release date: March 6, 2025

Available on: Quest headsets

Experienced on: Meta Quest 3

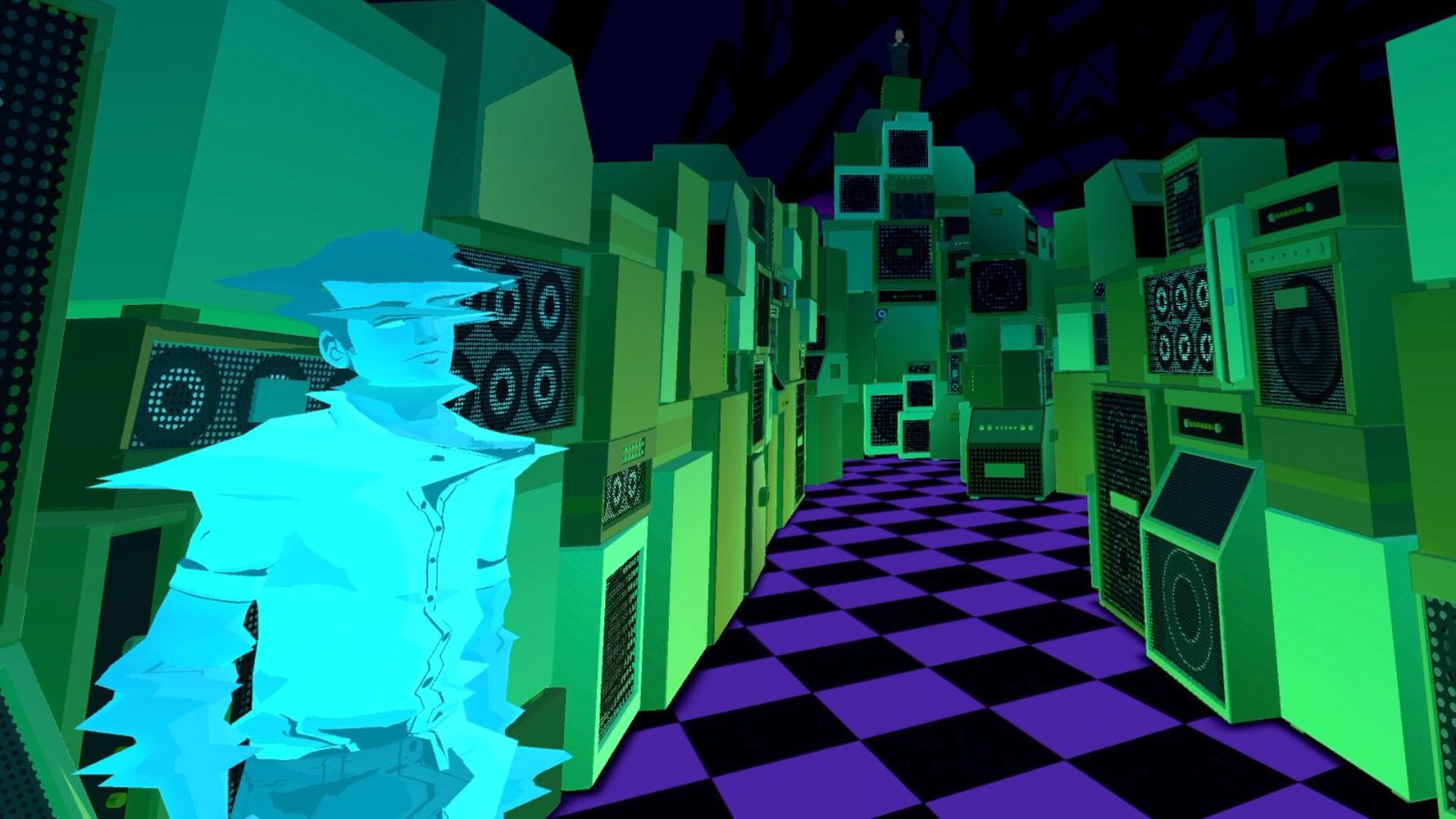

That’s absolutely not the case with Lovesick, a surreal narrative-driven puzzler set in the 1990s and centered character-wise around the player we embody, Sam, the bassist of a wannabe band. Their wastoid lives are interrupted when a phenomenon called “The Feedback” thrusts them into a parallel dimension, sort of like our world and sort of not, lit up like a gawdy pinball machine, and filled with glitching things that appear to have fallen out of the space/time continuum.

Lovesick arrives already looking and feeling a bit dated; god knows how it’ll play in a decade. The characters are quite well developed, with more nuance than most puzzle games, but navigating this world is a painful process, littered with maddening mechanics and immersion-breaking elements. Among the latter is the uncanny sight of characters who speak without their mouths moving, creating an audio-visual paradox: our eyes can’t believe our ears, and vice-versa.

The under-rated Wraith: The Oblivion – Afterlife (coincidentally, another horror game) also deployed motionless mouths but got away with it, more or less, because the people talking were creepy monochrome ghosts, throwing traditional notions of realism out the window. Lovesick begins with no visible humans in our immediate vicinity, opening at a gas station on a lonely stretch of highway, where we’re tasked with filling up the tank of the band’s van while a couple of members bicker inside.

We’re soon relocated to Sam’s stinky shared house, where we converse with fellow band members and fudge our way through rehearsal. The first person I engaged with was Dom, who declares we must “go back to bed” or “start drinking” (my kind of guy) and somehow says all this without moving his lips. Lovesick’s director, Corey Warning, no doubt has reasons for skimping on the whole “moving mouths” thing, almost certainly relating to time and resources.

But an important part of creative expression is understanding your limitations, and working within them (which sometimes, in fact, creates a valuable tension. This is what led Orson Welles to famously declare that “the enemy of art is the absense of limitations”). There are countless ways to approach narrative and gameplay. If you’ve arrived at a point where you’re asking people to look at humans who speak without moving their mouths, you’ve probably made some poor choices.

Lovesick’s restrictive navigation and penchant for frozen lips might not have been such a big deal, had the story really sizzled or the gameplay satisfied. The former is beholden to the latter, progressing upon the completion of various puzzles, most rather dull and, to me, poorly thought through (why, for example, are we asked to arrange the word “free” on a popcorn sign? What does that have to do with anything?). Making things worse are some very iffy mechanics. A case in point: about an hour in we’re granted an ability to pull objects towards us using a “wavelength” or “ethereal hand.” Which sounds simple but boy oh boy, this thing is hard to operate. At times I struggled merely to pick up an object, let alone place it anywhere.

Aesthetically, Lovesick brought to mind the surreal vaudevillian vibes of The Under Presents and Stranger Things VR, and the bong water-infused scuzziness of Battlescar: Punk Was Invented By Girls. Sound and production design are two of its strengths, though they’re nowhere near enough to compensate for so many infuriating elements. I played the game for about three hours, then called it quits.