Jurassic World Aftermath review: repetitive and laborious stealth

At least, in the Jurassic Park movies, people arrive on the island before things go haywire. In this VR game, the journey there is botched: we’re on a small plane en route to Isla Nublar (the island where the park was built) that gets taken down by massive prehistoric birds and crash-lands into a research complex. We spend the remainder of the experience creeping around here, trying not to get mauled by velociraptors while performing a highly repetitive series of tasks—i.e. activating power sources, locating various objects, turning knobs and dials, searching for pin numbers, and listening to audio tapes that deliver pockets of backstory.

It’s all staged competently, but Jurassic World Aftermath lacks colour and flair—nothing really pops, and after a while playing becomes laborious. Like countless other VR games we traverse this world alone—dinosaurs notwithstanding—with the exception of an engineer named Mia (voice of Laura Bailey) who accompanies us remotely and contributes extensive commentary, often in the form of instructions telling us precisely what to do. The aforementioned tasks, which will be very familiar to any gamer, often involve doubling back on previously experienced locations, maximizing their usage but adding to a festering sense of monotony.

Developer: Coatsink Software

Release date: December 17, 2020

Available on: Quest headsets, PSVR2

Experienced on: Meta Quest 2

It’s almost always clear what we need to do; Aftermath’s narrative structure is linear and uncluttered, as is the gameplay. After a while Mia begins to treat us as a quasi-confessional booth, fessing up about dubious past decisions, this plotline helping eke out the franchise’s key cautionary messages—about not messing with nature or pursuing scientific progress for purely capitalistic reasons. This dynamic never feels real: she talks and talks and we say nothing. And it feels quite contrived when Mia delivers lines like “while we wait, there’s another tape I need you to hear. I’m not proud.” It does however allow the experience to tell a human story without any humans being visually present.

Some simple touches work pretty well, reminiscent of how directors of thriller and horror movies pull the strings of suspense. Shortly after we arrive in the complex, for instance, we see a cute little dinosaur in an air duct; this is a directorial tool telling us to get in and follow it—leading to the first of much duct-crawling. Soon we start walking around hallways and see a velociraptor, but only just, experiencing the briefest of visions before it rounds a corner in front of us. Not long after, in another space, we see the creature walking above us, down a vent (more vents!) just for an instant. These anticipation-building flourishes reflect an understanding that things not shown, or shown briefly, can be scarier than those in plain sight.

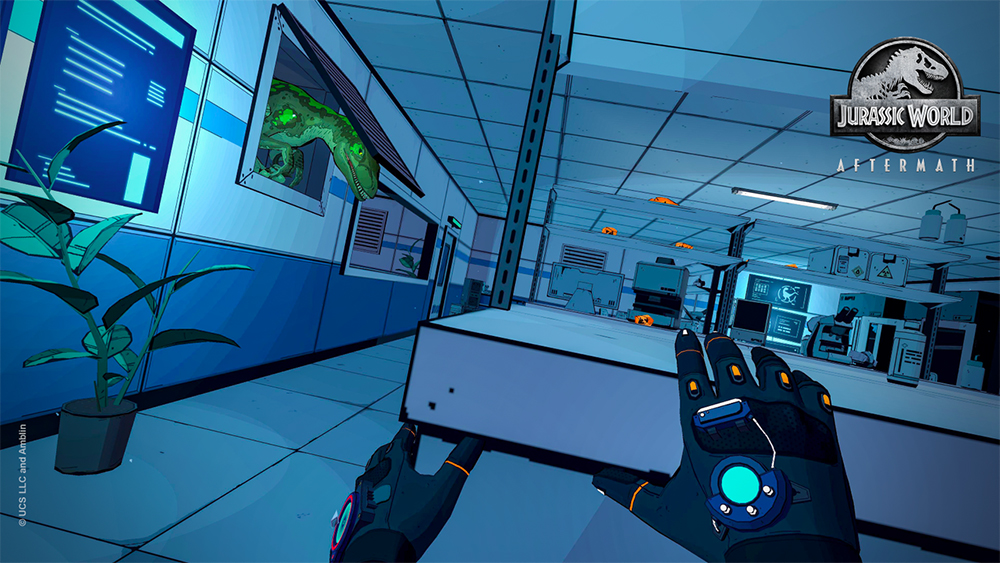

I’m fond of the game’s hand drawn, comic book-like aesthetic, but it really takes the edge off: it’s fun, not scary. During the many moments when the raptors are walking around, trying to sniff us out, we don’t feel on edge; at least I didn’t. Compare that to Westworld Awakening, a (vastly under-rated) game with similar stealth mechanisms. The atmosphere is gooseflesh-raising and the main villain, a cyborg named Hank, is a truly unsettling presence: we really don’t want him to catch us. In Aftermath, aspects of the sound design ratchet up, as if to compensate for the non- scary visuals, deploying for instance the intermittent sound of a heartbeat.

I appreciate VR experiences that deploy distinctive and highly stylised looks: the zany first-person shooter Fracked, for instance, and the monochrome horror game Wilson’s Heart. But in both these cases the temperament of their aesthetic fits the tone of the experience. Like its animation style, Fracked is kooky and fun. Aesthetically and thematically Wilson’s Heart homages creaky horror productions of yesteryear, including movies produced by James Whale and Hammer Films. There’s no such synchronicity in Jurassic World Aftermath. Creating suspense and dread is difficult at the best of times; here the production’s very form and texture work against it.

Perhaps, if the game had been less repetitive, or more narratively intriguing, I might not have noticed this as much. But there are many times to think and ponder in Aftermath: lots of long, windy dramatic passages in which we think “I’ve been here before.”