Evolution of Verse review: symbolically signficant cinema-homaging

Evolution of Verse is a short 360 video—less than four minutes long—but it occupies a symbolically significant place in modern VR. This elegantly made experience’s director, Chris Milk, screened it during a widely watched 2016 TedTalk, the same year virtual reality headsets first became available on the mass market. After placing VR within a continuum of expressive artistic mediums dating back to ancient times (“it starts around the campfire with a good story”) Milk went on to make a more specific connection: to the Lumière brothers legendary 1895 film L’arrivée d’un train en gare de La Ciotat (The Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat Station).

“We are the equivalent of year one of cinema,” he said, before teeing up Evolution of Verse. It features a rousing early moment that spectacularly homages L’arrivée d’un train en gare de La Ciotat, ushering the train into virtual existence and illustrating how VR has revolutionized the relationship between content and consumer.

Developer: Flight School Studio

Release date: January 12, 2023

Available on: Quest headets

Experienced on: Meta Quest 2

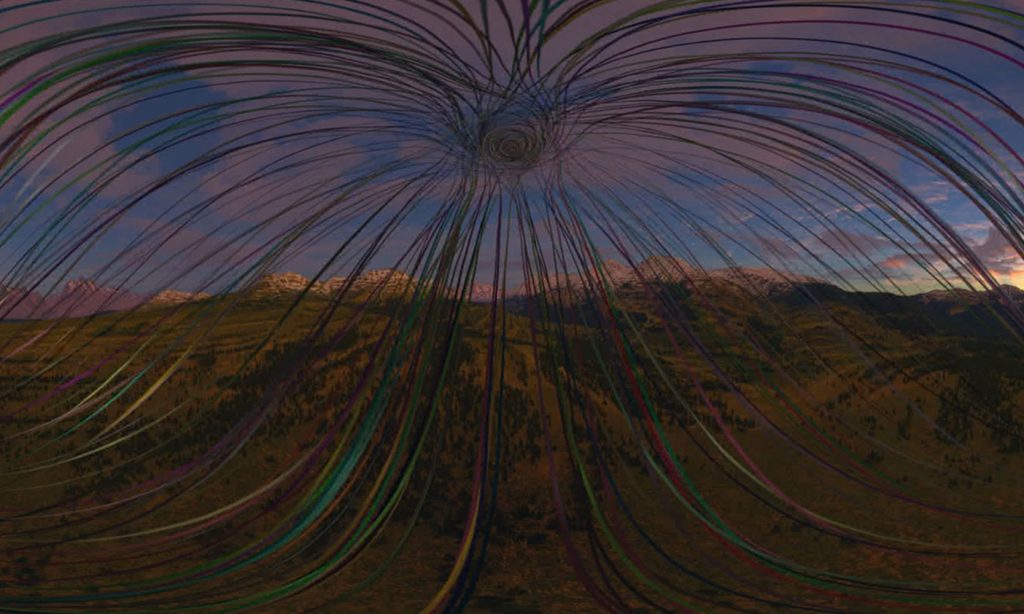

It begins with the spectator situated in the middle of a lake rimmed by snow-capped mountains, accompanied by a meditative score by McKenzie Stubbert, matching the sounds of birds twittering with a sustained synth note, leading into arpeggio piano as the sun ascends. Its rising occurs at an accelerated pace while, close to us, dragonflies buzz around at a realistic speed—marking a disparity in the temporal flow between foreground and background.

The music and ruminative sounds of the creatures continues before the introduction of a dramatic addition to the aural landscape: the whistle of a steam train. Billowing a large trail of steam, the train moves from behind trees in the distance before taking a dramatic turn, moving onto the lake itself and barrelling towards us. This of course evokes the Lumière film. Many historians sensationally recorded the arrival of the train in this early motion picture as a moment that made audiences scream, jump and lunge from their seats, though this has subsequently been debunked by scholars such as Martin Loiperdinger, who described the audience’s alleged behaviour as a “generally agreed-upon rumour.”

Back to Evolution of Verse: the train rapidly approaches as water spurts off its cowcatcher. Right at the moment of impact, just when the vehicle is set to collide with us, the music bursts into a soaring orchestral score and the train disintegrates into a flock of black birds that move and streak across the sky. What a moment! It’s visceral and beautiful, supercharged by history, legend, and various metatextual connections. The virtual camera then rises into the sky, into a darkened space-like tableau, where it moves around the edges of a planet-like dome, which is revealed to be the head of a baby—sucking its thumb, umbilical cord still attached. Just as the train’s arrival drew a clear cinematic comparison, this one does too, recalling the famous “star child” sequence from 2001: A Space Odyssey.

But the train scene is the real gold; the experience’s raison d d’etre. The TedTalk video shows the audience smiling, marveling, and turning their heads at the moment of impact, wowed by the spectacle (rather than running for their lives). It’d be foolish for people writing about VR to make the same mistake as those who erroneously reported the reaction to L’arrivée d’un train en gare de La Ciotat. And yet it’s unquestionably true that VR is a more immersive medium that solicits more visceral responses.

One popular, carnival-like production from the present era (2016 onwards) is Richie’s Plank Experience, in which players are taken 80 stories high up in a virtual skyscraper, then prompted to walk onto a plank of wood protruding from the building. For increased effect, an actual plank can be placed on the ground and synced with the virtual one. I’ve seen people participating in Richie’s Plank Experience who really did seem to be fearing for their lives; one young woman at a VR conference I attended several years ago wailed like a banshee.

These kinds of responses aren’t uncommon. Many scholars have studied them over many years. Perhaps their findings can be simplified as our minds yelling at us: “holy shit, something’s wrong, move!” When I introduced my mother, who was in her early 70s at the time, to Beat Saber, there was a brief moment when I thought I might have killed her. She was getting into it, slicing and dicing and bobbing about, until a huge block barrelled towards her. Instead of ducking (as you’re supposed to) she screamed, completely freaked out, then attempted to run away from her own face.

These responses come from an increased sense of presence, borne from a revolutionized relationship with the screen. Instead of watching a sectioned-off area of representation (like in film and TV) that’s somewhere else, somewhere other, in VR we share the same playing space as the imaginative world. As VR evolves and spatial computing becomes more entrenched in popular culture, tiers of virtual and physical realities irrevocably merged and overlaid, such observations may feel increasingly passé—as will, of course, content I write about in the present era.

It didn’t take long for Evolution of Verse itself, in fact, to look a little dated, being a short (non-interactive) video that’s fairly simplistically staged. However its relative simplicity is also a virtue. And its symbolic significance means this brief but memorable experience will stand the test of time.