Astra review: transforming your living room into a spaceship

Eliza McNitt’s mixed reality experience will transform your living room into a spaceship and send you hurtling through the galaxy, making pit stops at various planets to collect natural resources. Like all mixed reality experiences, the game contrasts inner and outer spaces: the former drawn from the physical world and the latter virtualized, here with the double meaning of outer space referring to journeys across the cosmos. The challenge is to create a dramatically engaging and emotionally satisfying experience from this synthesis—which is partly realised here, the production impressing on several levels.

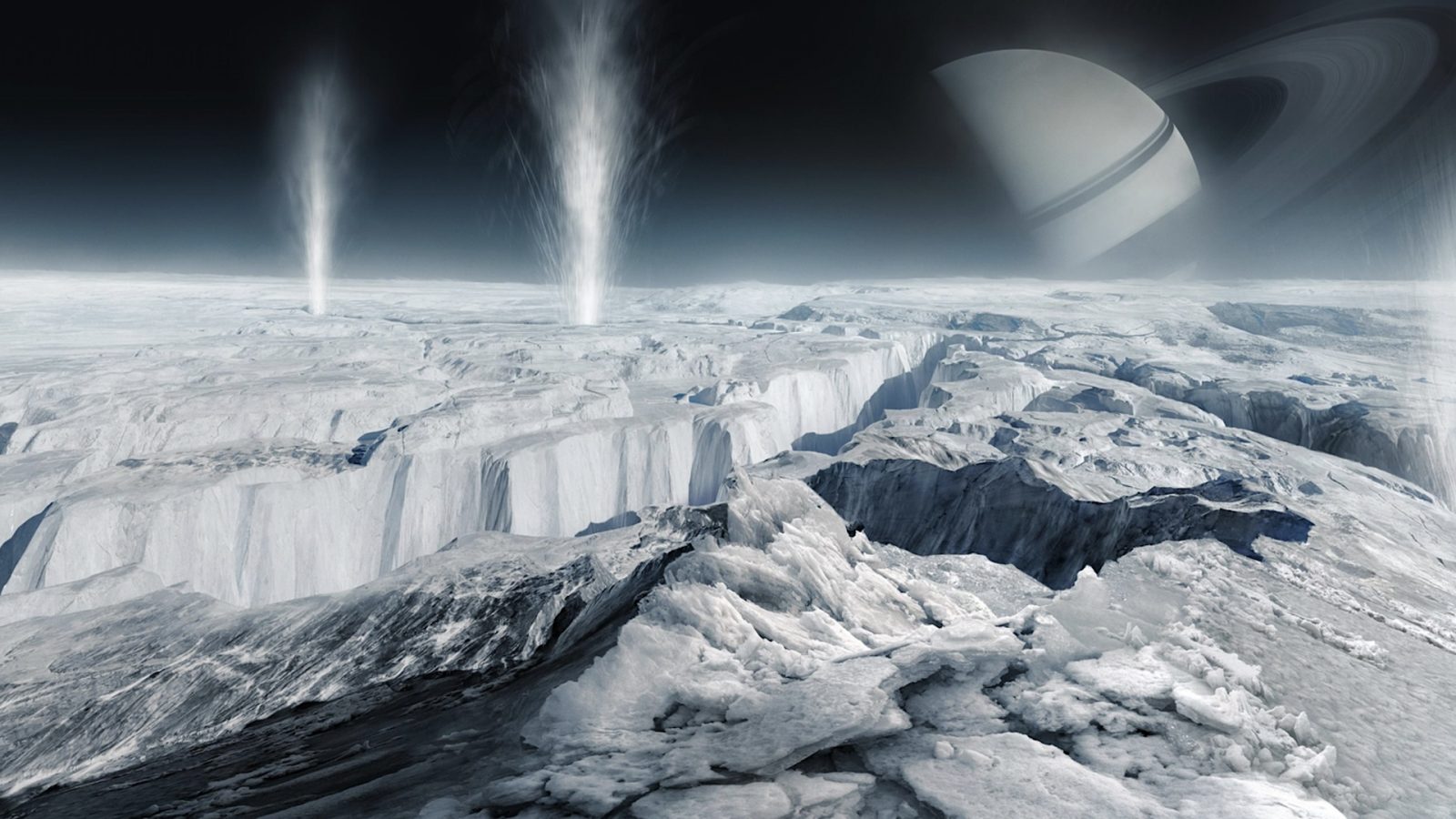

A large virtual window or space observation deck replaces your wall of preference, while real world elements remain. For me, my spiffy new vessel had old school touches—including a chesterfield armchair and my collection of Nicolas Cage DVDs. So it’s sort of your environment and sort of not. Places visited include Jupiter and Saturn’s moon, Titan; once we select the relevant location (although there’s not really a choice—this is an on-the-rails experience) we see our refitted room seemingly travel through space, other planets and the dark blanket of the galaxy observable through the aforementioned window.

Director: Eliza McNitt

Release date: April 25, 2024

Available on: Meta Quest 3

Experienced on: Meta Quest 3

These moments contrast foreground and background, applying motion-like effects to create the illusion of movement. It’s a classic visual trick used in many immersive spaces, from cockpit simulators to theme park rides and planetariums. McNitt knows the mixed reality element will get people through the door (so to speak—we’re not leaving the house), selling the experience on the aforementioned novelty of your own room becoming a rocket ship.

The input the experience requires from us, through its 40-ish minute runtime, is better described as interactive elements rather than gameplay per se. Like McNitt’s striking space-set VR experience Spheres, which turned heads when it arrived in 2018—becoming the first VR production to be sold at Sundance Film Festival in a seven figure deal—the interactivity in Astra is deliberately limited, augmenting a heavily curated experience featuring narrative elements, voice-over components, and an escalating sense of mystery and wonder.

Spheres makes us the size of a god, turning planets into tennis ball sized things we bounce around and listen to. Astra returns us to human size and form. It begins on a personal scale, with a box placed in the room, text drawn on it reading “FOR CHARLIE, mum wanted you to have these. Dad.” Inside are random items including a lamp, a toy rocket ship, posters, and a cassette recorder and tapes.

Anybody who’s ever played a video game can guess what happens next: once loaded the tapes will play a voice delivering narratively pertinent information. For a technology format that went the way of the dodo a long time ago, there sure are lots of cassettes in video games, used (like the also popular computer “audio log”) to trigger expositional outlays. In Astra we hear the soft voice of a woman clear her throat and leave a message “for future worlds and far away beings,” reflecting on how she’s traveled the universe via a telescope, but one day, she says, we won’t just look from afar: “we will walk on other worlds.”

After this prologue, the ship forms around us, and a circular disc-like robot appears to help guide us through how everything works, explaining the functions of various apparatus. We’re shown how to travel to various planets by using a dashboard interface; once we arrive at the planet in question, we stand beneath a teleporter and are taken there. Once on the planet, the production switches from mixed reality to wraparound VR, in my case ditching the armchair and Nic Cage DVDs. This segue works well, the teleporter a satisfying conduit between worlds.

After collecting resources from a few planets—carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, etcetera—the experience enters a trippy final stretch as we enter “Interstellar” space. This section ruminates on The Golden Record (a real-life disc containing sounds and images of earth) and uses it to springboard into a strange, imaginative arena, moving from an experience based in the known to a big speculative chunk based very much in the unknown, with a cautious message about exploring the universe through human-centric perspectives. This bold final section gives Astra a memorable kick.