Emperor review: richly emotional and strikingly surreal

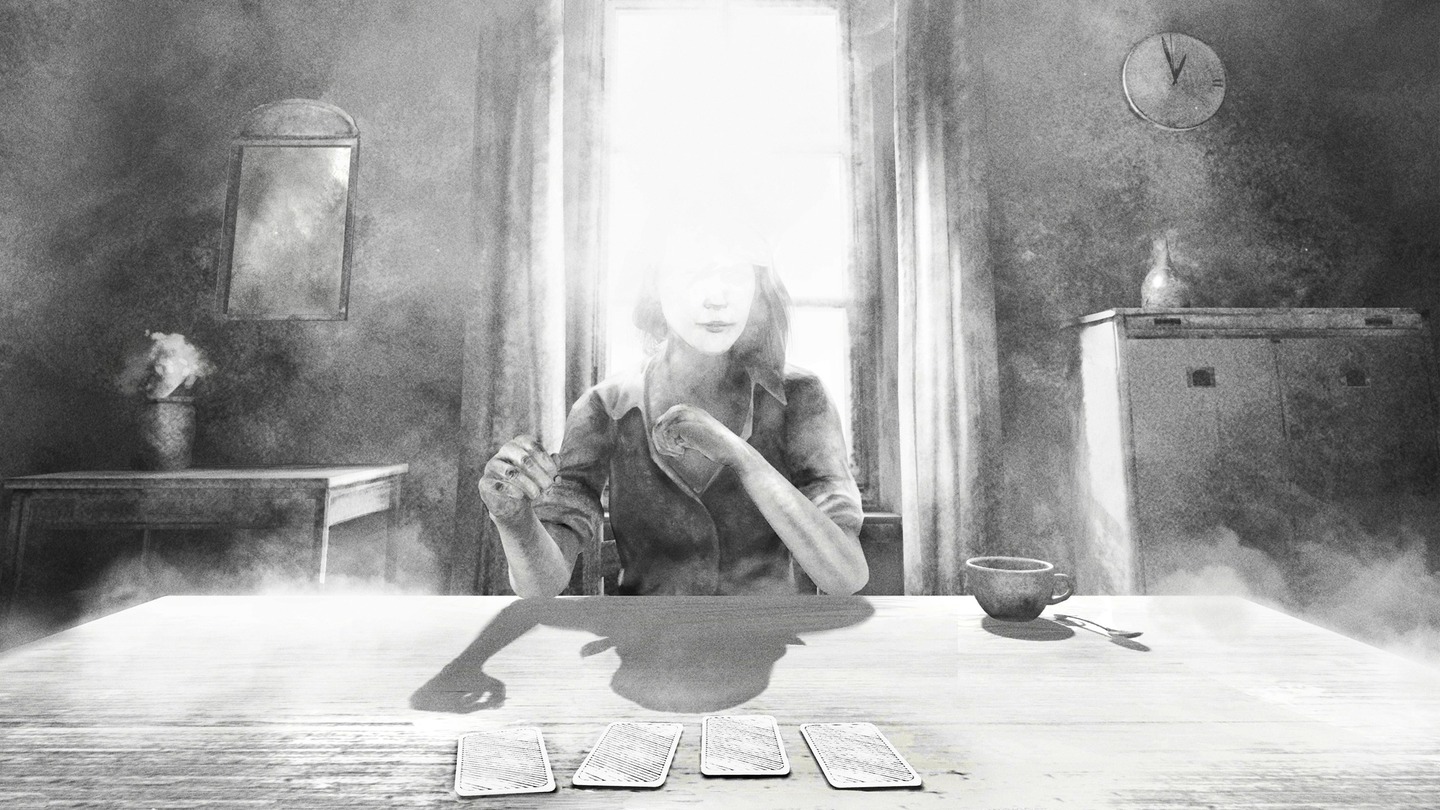

This 40-ish minute narrative experience from directors Marion Burger and Ilan Cohen unpacks the poignant personal story of a man who developed a condition known as aphasia, defined in an introductory text insert as “a language and communication disorder due to brain damage, often accompanied by partial paralysis of the body.” Visually the production is presented entirely in hand-drawn-looking, charcoal-like monochrome, but emotionally speaking it’s coloured with feelings—some subtle, many powerful and moving.

Emperor is elegantly made, aesthetically prioritising white over black, which gives it a bleached light-filled complexion. It looks snowy but doesn’t feel cold—due to the richness and warmth of the story and the perspective from which it unfolds. Burger recounts what happened to her father and unpacks his condition, explaining that he now “understands everything but can no longer be understood.” She resolves to come to terms with the human being that “got broken that morning,” when he suffered a stroke and was never the same, suffering from the aforementioned condition.

Directors: Marion Burger and Ilan Cohen

Year of release: 2023

Available on: Quest headsets

Experienced on: Meta Quest 3

That preference of white over black, with washed over visuals that have a lovely, smudgy, tactile feel, symbolizes optimism over despair. I was reminded of a line from a Leonard Cohen song: “there is a crack in everything, that’s how the light gets in.” Emperor also reminded me of two short VR experiences: Notes on Blindness—which explores the process of going blind, also anchored by a very personal focus—and the mixed reality production Turbulence: Jamais Vu, which uses a modified headset to simulate the effects of a chronic vestibular condition.

In one scene in Jamais Vu, we’re asked to achieve a theoretically simplistic task: retrieving some aspirin from a container in front of us. This proves very difficult, however, because the creators have warped our sensory information, blurring and distorting our vision. A similar moment occurs in Emperor when, having embodied Burger’s father, we’re asked to perform basic tasks such as spelling the last three letters of the word “December.” We’re made to fail these exercises, simulating the experience of knowing something but being unable to express it, our communicative abilities short circuiting.

Burger and Cohen contrast intimate moments like these with large surreal set pieces, including a sparse desert-like environment with howling winds and a massive statue of a man dressed in a toga, jutting through the clouds like a Greek god. This is the last frontier of the old man’s mind: the ruins of his psyche, scattered with detritus from the past. It folds together then and now—one foot in reality, the other in a dreamy hypnagogic state.

In one scene we look up and observe fingers as tall as mountains rising from the ground; in another we’re required to turn the handle of a door several times, on each occasion triggering a sound recording of a moment from long ago, between father and daughter. Interactive elements are minimal, just splashes here and there. These generally require small actions, such as moving towards predetermined nodes by pointing at them or picking up objects, including in one bizarre embellishment what appears to be a fish lodged in the ground; when we retrieve it we discover it’s half sea creature, half wine bottle.

Many of the spaces and flourishes are trippy, but despite its atmospheric audaciousness Emperor always feels emotionally real. Both father and daughter appear in it, at different times, though we never see the entirety of their faces. This, for me, increased the intimacy of the experience, adding a degree of universality, suggesting that while this is their story but it’s also shared by or indicative of many others. This is powerful work: tender and strikingly immersive.