Wraith: The Oblivion – Afterlife review: spatially interesting horror

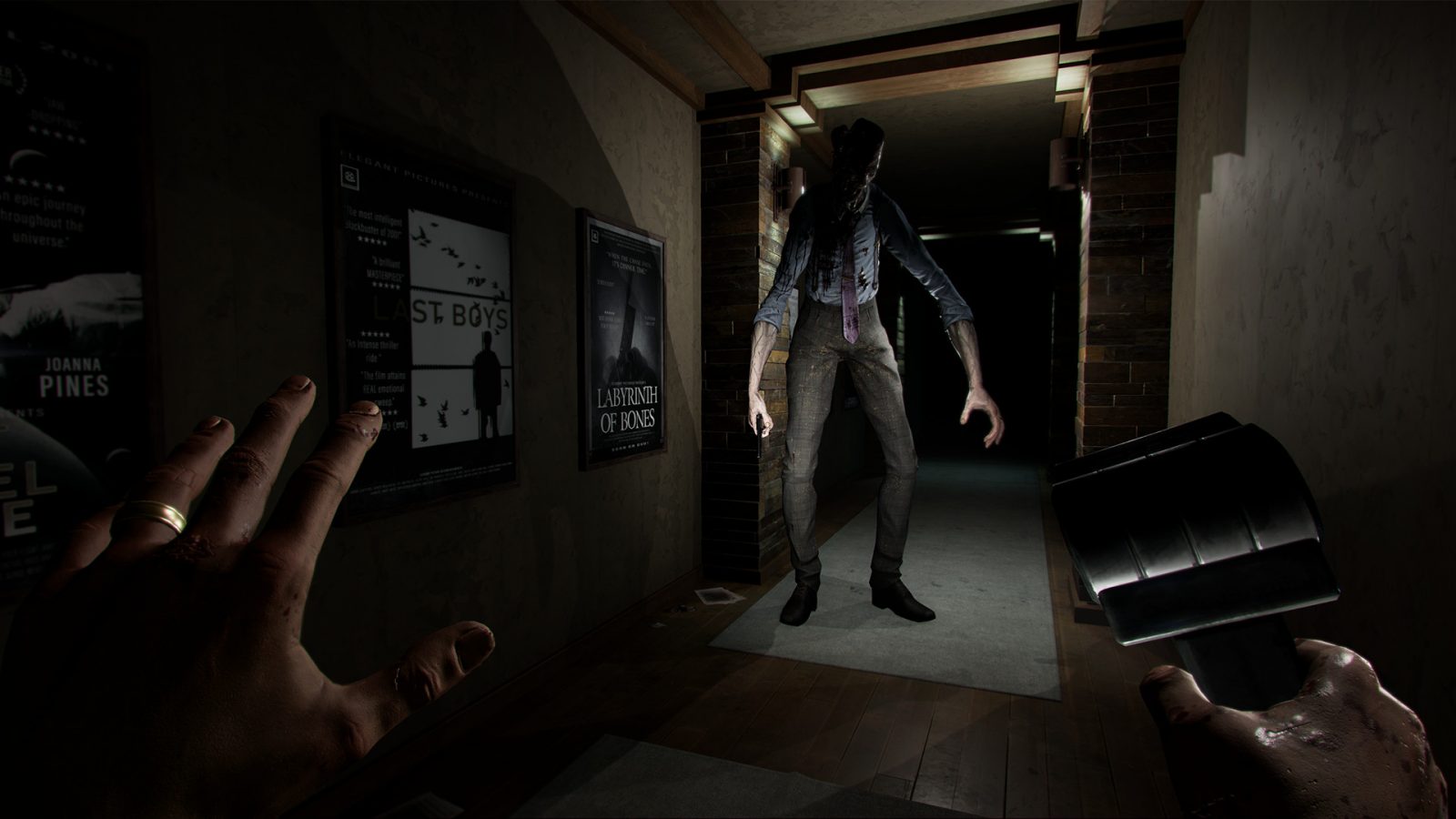

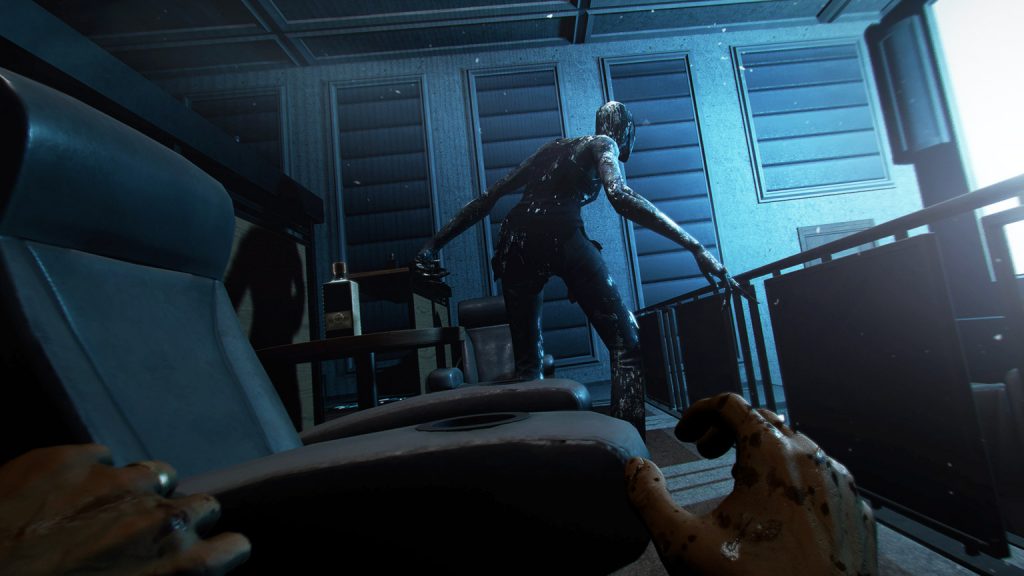

This intensely engaging and very creepy game takes place in an almost impossibly large modern mansion, owned by a Hollywood billionaire, where some years ago a handful of people died during a seance. We play the ghost of one of them, a photographer with no memory of what happened, learning more as we navigate through the house, which involves sneaking past hideous ghouls that’ll rip us to shreds if we’re spotted.

A voice in our head delivers running commentary, which is fairly common in VR games, but here there’s an eerie twist enabled through spatial sound. The voice seems to come from a particular direction but if we turn our heads towards it, it changes to some other place, like a demon bouncing around our brain.

Developer: Fast Travel Games

Release date: April 22, 2021

Available on: Quest headsets, Steam, Oculus Rift, PSVR

Experienced on: Meta Quest 3

That voice in our head notwithstanding, this is a lonely experience, clear from the outset that our job is to explore this world rather than interact with others. Human characters do however periodically appear, in predetermined scenes rendered in black and white, gradually filling in the backstory. These moments are the equivalent of movie flashbacks, but, crucially, they’re brought into the environment we inhabit, allowing the game to maintain spatial unity while revealing events from the past. VR is all about using space to reveal information, and this is a great way to do it, similar to how backstory-delivering ghosts are deployed in The Seventh Guest VR.

One of Wraith’s more interesting flourishes is the addition of an ability dubbed “sharpened senses” that helps us navigate. It’s a hot and cold system that works by pressing a button then moving your arm, which, if pointed in the right direction, will light up and prompt the controller to vibrate. It’s a simple touch but it has a striking effect—combining haptic and visual—and shows the developers thinking about how to create unique VR elements, furthering the nascent medium’s language and syntax.

In addition to many fetch missions, there’s a lot of stealth in Wraith—for instance crawling past ghosts, hiding, and throwing bottles to distract them. This slows down an already slow paced game, though “slow” in this instance is not a pejorative. Quite the opposite: the atmosphere is skillfully drawn and highly involving, based not on cheap jump scares—like Five Nights at Freddy—but an atmospheric form of dread that creeps under your (intermittently vibrating and glowing) skin.

Some of the small touches resonate, again showing the game using space to reveal information. At one point we walk past a bar into a large room with a humongous tree growing inside; this world is so depraved even nature has turned against it. We soon discover we need to return the way we came from, but when we do, there’s a man hanging from the tree, coughing and wheezing, who wasn’t there before. It’s very creepy, injecting the known with the unknown. And the game forces us to walk right below where this doomed fellow is hanging.

Throughout the game you’ll encounter lots of locked doors. Bumping into them reminded me of my first immersive theatre experience, a Sleep No More inspired riff on Edgar Allan Poe’s The Tell-Tale Heart, which had lots of locked doors; sometimes I followed an actor, watching them go through one while I was left behind. These doors were then opened at strategic points, as they are in Wraith: a clever technique that encourages us to appreciate the reveal of new spaces, and the simple act of entering them.

The gameplay is certainly repetitious, and the backstory-heavy narrative at times slips away, while we go through the slog of sneaking from A to B. But this is classy, layered psychologically layered horror.