Reeducated review: matching verbal testimony with spatial reveals

Created as a companion piece to a longform article published in The New Yorker investigating secret detention camps in China, Reeducated is a visually engaging 360 video that has a good—perhaps the best—answer to the question “why tell this story in virtual reality?” That question is always important, but perhaps especially so here, given the existence of the aforementioned article: a rigorously researched exposé containing a level of detail, including statistics and historical information, that couldn’t fit into an immersive experience.

The answer is all about space. Director Sam Wolson understands that good VR storytelling involves revealing information spatially. In VR, settings and narrative are wrapped together like a double helix: stories belong to spaces, and spaces tell stories. In this case a very grim one about propaganda-filled prisons where human beings are, indeed, reeducated, though “brainwashed” would be an acceptable synonym.

Director: Sam Wolson

Year of releasse: 2021

Format: 360 video

Experienced on: Meta Quest and Meta Quest 3

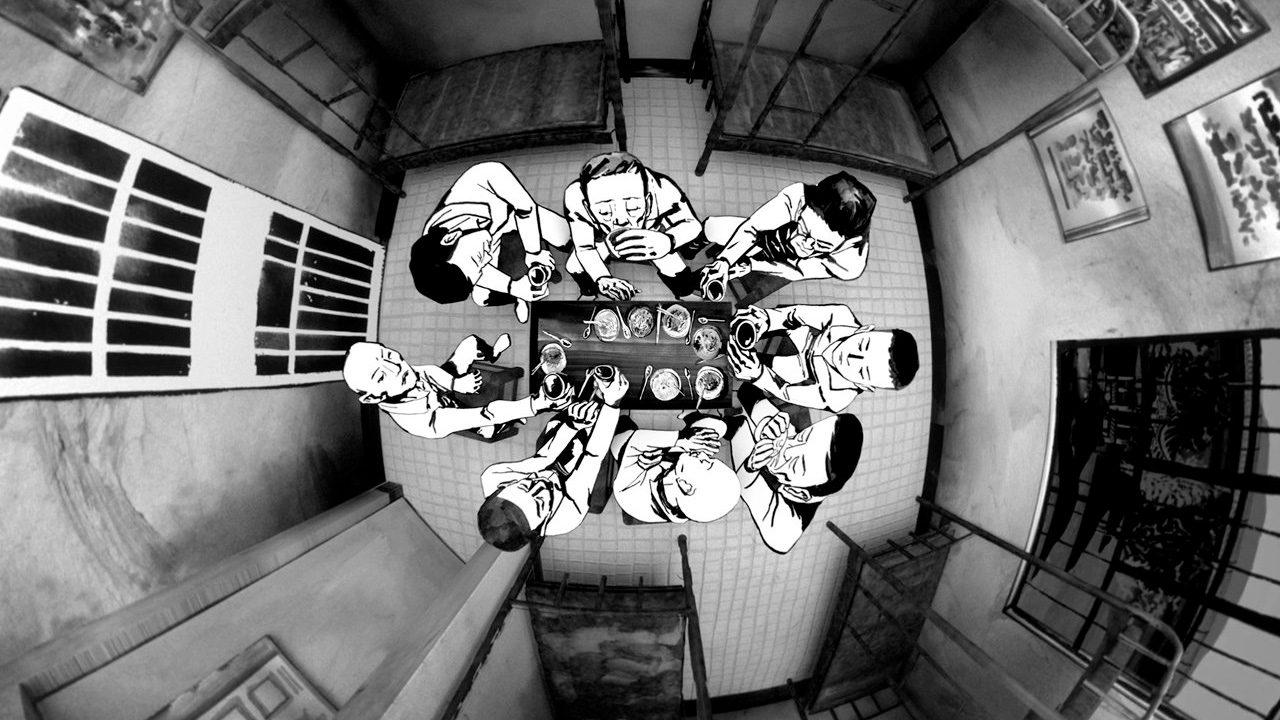

Vividly depicting one of these prisons was always going to be a challenge, relying wholly on the testimonies of previous detainees. Instead of attempting lifelike renderings Wolson deploys a highly stylised monochrome aesthetic, imbuing the fabric of the experience with harshly expressive qualities that reflect the emotional essence of the camps, its black and white textures feeling coarse and cruel.

People—both guards and inmates—are depicted in two dimensional forms, like cardboard cutouts, reiterating that their depth and humanity have been stripped away. Visual contrivances like this can be immersion breakers, but here, in a world reimagined from the ground up—with no fidelity to realism—it has a striking effect.

We first see these illustrations during a short prologue (the full video runs for about 20 minutes) introducing three key subjects, who grew up in Xinjiang, immigrated to Kazakhstan, and came back to China, where they were imprisoned. They are Amanzhan Seituly (who “flew to Beijing on business and was detained at the airport”), Orynbek Koksebek (who “was visiting family members following the death of his father”) and Erbaqyt Otarbai (who “was working as a truck driver for a Chinese mining company”).

The ensuing experience bears some broad similarities to the Guardian-produced 360 video 6X9: A Solitary Confinement, in that it renders the prisoners’ grim living quarters. But Wolson doesn’t just plonk us into this space; he reveals elements slowly and tactfully. While one of the subjects reflects that “if you stand in the center of the room, facing the door, you see a small eye-shaped camera,” that camera appears in the space above us, before the walls of the room are visualised, stretching out in the darkness.

When the subject notes the location of various elements (i.e. “here is the toilet” and “here is a bed where I slept”) they then appear, his words summoning them into existence. A similar technique—matching verbal testimony with spatial reveals—was also put to highly effective use in the 2016 VR experience Notes on Blindness, which visualises and spatialises theologian John Hull’s extensive cassette recordings about losing his sight. Reeducated also crafts environments not just to reflect the factual truth of what happened, but the emotional truth of it too.