Battlescar: Punk Was Invented By Girls review – sensorial candy

I love the energy and exuberance of this experience; I love its pluck and sass. The developers of Battlescar: Punk Was Invented By Girls embraced an “everything and the kitchen sink” approach, tossing around all kinds of in-your-face visual embellishments to tell the story of two women in 1970s New York who meet, form a band, and indulge in various kinds of badassery. It’s non-interactive, though it bends over backwards to evoke a feeling that you’re doing more than watching. This beast of a production has real visceral oomph; it’s something you can’t help but feel—like sticking your head out the window of a fast-moving vehicle.

Illustrators Nico Casavecchia and Martin Allais might prefer the following analogy: watching Battlescar is like standing on the edge of a station platform as a train whooshes by. This is indeed where we find ourselves, close to the beginning, after the protagonist and narrator—a Latino teenager named Lupe (voiced by Rosario Dawson)—has met her nogoodnik new friend Debbie, who always causes trouble and drags others into the mess. Wanting to impress her, and compelled by the idea of starting a band, Lupe lies and says she can write lyrics. The pair hang out in dark slummy settings, steal things from shops, rehearse, and seek advice from a heroin-using muso in the lead up to their first gig.

Developer: Flight School Studio

Release date: January 12, 2023

Available on: Quest headets

Experienced on: Meta Quest 2

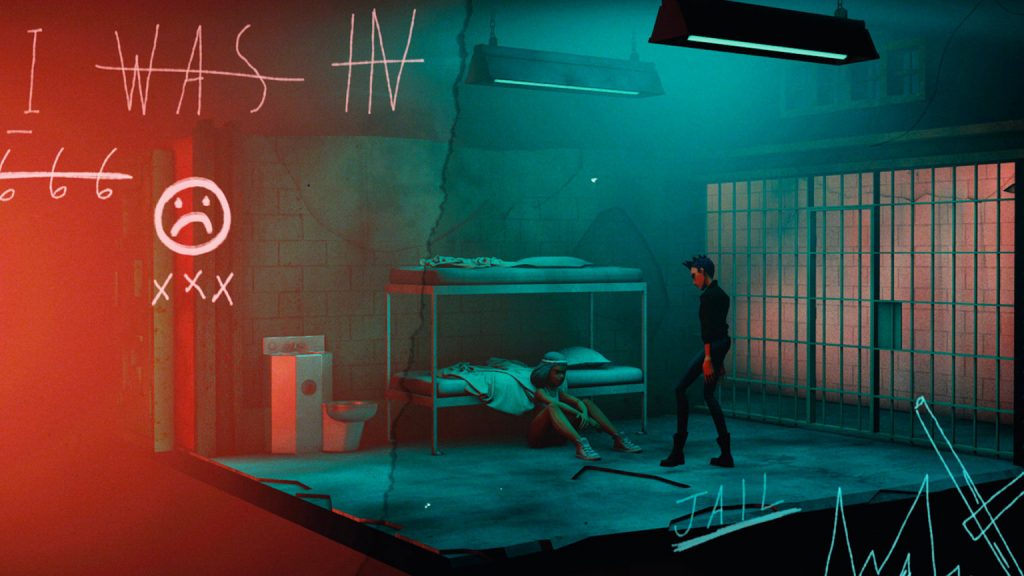

Battlescar throws around all sorts of interesting visual concepts. Sharp contrasts in size and scale are strewn throughout, including transitions into the widely used diorama effect—condensing key settings into dollhouse-like edifices, evoking a sense of godliness in the observer. Many productions embrace this perspective as a core feature (including Paper Birds, Allumette, Gloomy Eyes and Ghost Giant), but here the effect is striking partly because it’s jarring. One moment we’re on ground level, watching Lupe in front of a mugshot background, the blackened out space around her concentrating our visual attention; the next we’re hoisted into the air, looking down on a police cell where the two principal characters meet.

Casavecchia and Allais explode any notion of a continual, anchoring form of presence by intensely displacing the spectator. Inserting printed words displaying dialogue into the virtual tableau is textbook non-diegeticism, used here not for the purpose of subtitles but to visually scream. Here’s some bling! And some more!! And more!!! It might’ve been grating if it wasn’t so exhilarating, signifying a production that works hard to sustain attention—and doesn’t take a moment for granted. The dialogue text is sometimes spatially layered, some words closer to and others further away, allowing us to move our heads through and past them.

This is a technique you don’t see a lot of—partly because it draws attention to text, making its presentation a feature, rather than something simply absorbed. And also because it’s rare for words to be thematically germane to the experience. Here they are (because Lupe is an aspiring lyricist) as they are in the terrific Dear Angelica, about a young woman who writes letters to her late mother, her words curving and coiling and decorating the air with striking dimensionality. In Battlescar, there’s a suite of layering techniques: for instance a “GREETINGS FROM NEW YORK” postcard you can stick your head into, examining stylish cardboard-esque cutouts.

About 10 minutes in (the total runtime is about half an hour) Lula jumps on the back of a motorbike stolen by Debbie, and we assume a position on her seat as the lead-footed speed demon fangs it towards 48th street and 7th Avenue, graphic novel-esque impressions of the city whooshing by. This visual configuration is conceptually similar to a theme park ride, the viewer or player in a fixed position as the virtual space moves forward. When you can’t control the ride, this configuration tends to quickly lose its luster. But in Battlescar it only lasts for about 10 seconds—just another bit of bling to indulge our senses.

In coming years, when the graphical quality of VR experiences far exceeds the current standard, VR developers might like to revisit Battlescar for ideas about visual elements to expand upon. I can’t wait to see what they look like as the technology evolves. That’s not to say these ideas here are particularly original—but there’s tonnes of them to choose between, served up like a smorgasbord of sensorial candy.