6×9: An Immersive Experience of Solitary Confinement review: exploring imprisonment

In his influential book The Language of New Media, scholar Lev Manovich makes many compelling arguments about the nature of virtual reality. One of them is countering the idea that headsets liberate the user in hitherto unimaginable ways. In fact, he argues, very much against the grain, “VR imprisons the body to an unprecedented extent.” In this context the scholar is discussing our actual body, not our virtual one—though both are imprisoned in 6×9: An Immersive Experience of Solitary Confinement. Watching this short 360 video, which has stuck in my mind despite its brevity—being just two minutes and fifty seconds long—reminded me of Manovich’s words, prompting me to contemplate them anew.

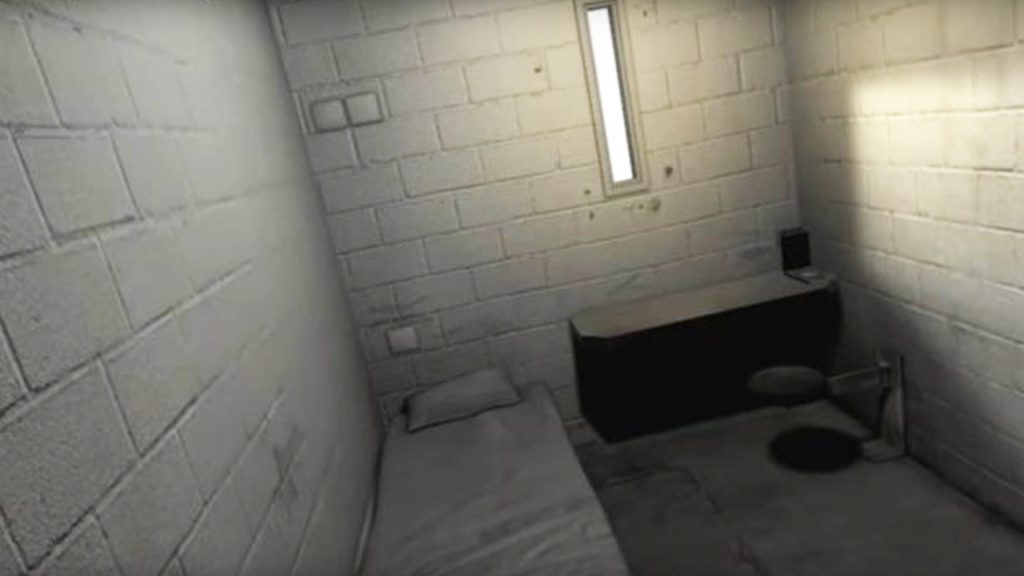

It was produced by The Guardian, which, like several major media outlets, dabbled in VR around the time headsets became consumer-available devices (circa 2016). The experience is entirely based in a prison cell—making it metaphorically rich as a commentary on powerlessness in VR, as well as a very literal representation of it. At no point do we leave our dirty, sparsely furnished cell, which is six feet wide and nine feet long, with a single bed, a desk and a toilet. In other words: it ain’t the Ritz. This speaks to the point of the production: evoking spatial awareness of what living in a room like this would be like—and by turn evoking empathy for the incarcerated.

Directors: Francesca Panetta and Lindsay Poulton

Year of release: 2016

Format: 360 video

Experienced on: Gear VR, Oculus Go

6X9 begins in pitch black, muffled sounds of a police radio accompanying text inserts that establish an emotional and empathetic context. The first reads: “Right now, 80,000 – 100,000 people are in solitary confinement in the US.” The second: “They spend 22-24 hours a day in concrete cells, with little to no human contact for days or even decades.” We get our bearings and come to terms with the room, its off-white walls splotched with stains. Light trickles in through a thin vertical window a few centimeters wide and a couple of feet tall. This is, to state the obvious, a depressing environment, cold and sterile.

“Welcome to your cell,” a voice-over narrator says. “You’re going to be here for 23 hours a day.” An assortment of voices start speaking, listing things “you can be sent to solitary for,” which include “disobeying a direct order,” “yelling too loud,” “any kind of drugs” and “looking at a correction officer.” As we hear these words they appear in written form around us. Text reading “yelling too loud,” for instance, is stamped across the wall above the door to the cell. These non-diegetic flourishes reiterate key messages, but at a cost—reminding us of the mediated nature of the experience.

We never leave the cell or see any human faces, but a sense of shared experience is evoked—entirely through audio. At one point a psychologist explains that inmates mentally “undergo many kinds of reactions.” This procedes a simulation of these reactions, which deploy horror movie-like effects: things come in and out of focus; cracks appear on the walls, spreading like terrible vines; and the sound of water goes drip drip drip, drip drip drip. These flourishes tip the experience into a deeper psychological domain.

Back to Manovich: in 6X9, VR’s imprisonment of the body is illustrated in the literal setting of a prison cell—but the most debilitating powerlessness arises from our lack of agency within it. This is a 360 video, therefore we have no hands or legs, and no ability to navigate this space ourselves, our placement in the scene dictated by the camera. This is dramatically reflected during one moment when it rises into the air, forcefully pulling our virtual selves up with it. Here we’re aware of another kind of powerlessness: having presence within a virtual world, but no agency or input.