The Book of Distance review: tenderly personal embodied history

Randall Okita’s tenderly crafted production unfolds like an experiential family photo album or embodied history lesson, exploring the story of his grandfather Yonezo Okita, who migrated to America from Japan in the 1930s. The Book of Distance begins, in fact, with a virtual photo album appearing before us; we open it to discover three pictures on the left page and a horseshoe atop the right. Once we pick up a photograph of an elderly man and a child, Randall begins speaking: “those images are of my grandfather Yonezo,” he says. “I’m the kid in that one.”

This opening statement suggests yet another VR production verbally steered by an unseen narrator. But something unexpected happens: an animated version of Randall himself emerges from the darkened tableau around us. The experience feels personal and familial from the start, but this entry changes the dynamic; we’re now being welcomed into his space. Randall acknowledges the horseshoe and draws attention to an area located leftwards, where it’s to be thrown. “You have to look where you’re going,” he says. “Keep your eyes forward and follow through with your hand.”

Directed by: Randall Okita

Release date: January 20, 2020

Available on: Steam VR, Oculus Rift

Experienced on: SteamVR using Quest 2

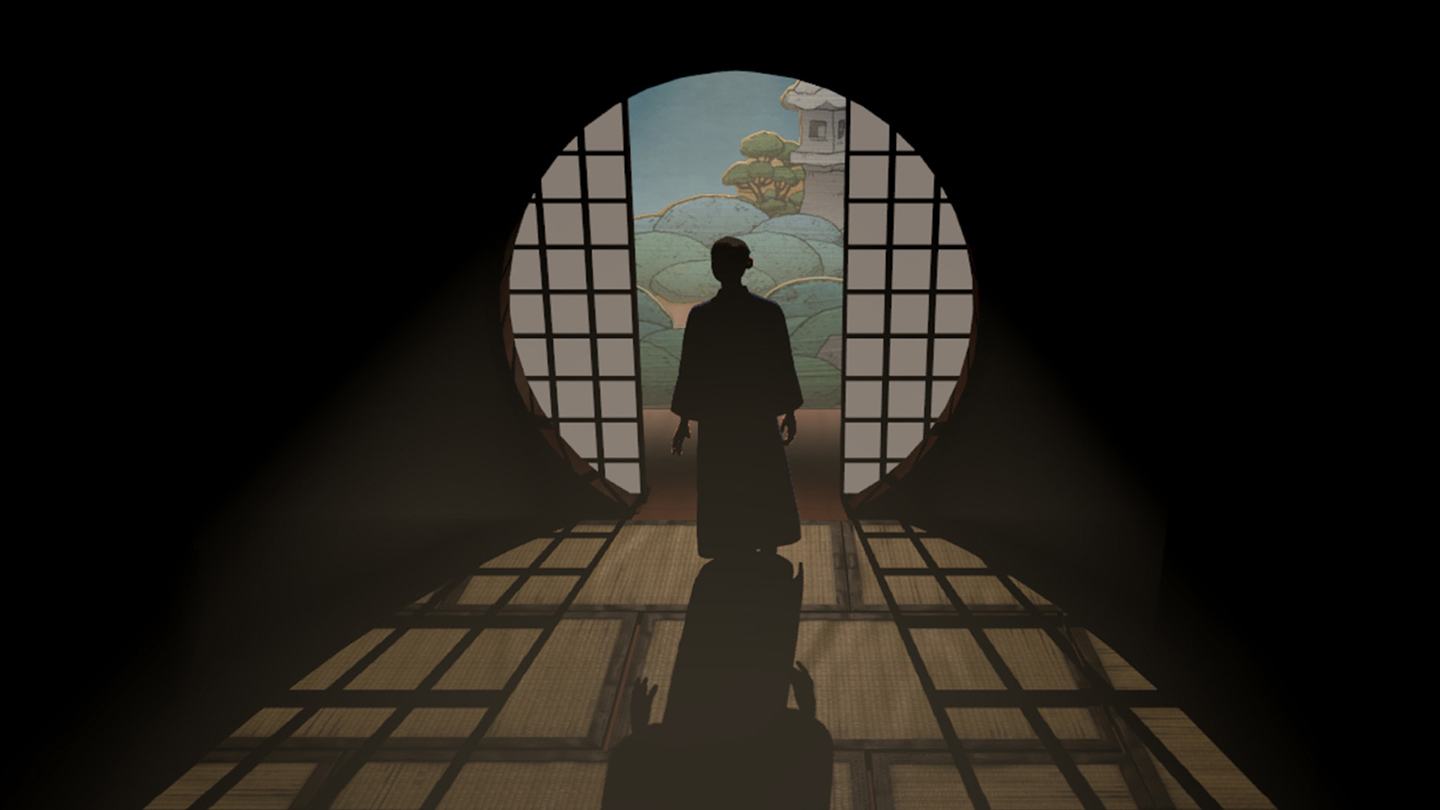

This moment endears us to the host/storyteller and establishes a sense of rapport. We know we cannot talk back but it doesn’t matter: this is his family, his history lesson, his grandfather’s tale. We’re guided through it with a warm embrace. The next half hour or so consists of Randall introducing soundstage-like environments depicting different periods in his grandfather’s life—beginning with his upbringing in Hiroshima in the 1930s, presented via a virtual set of a traditional Japanese household from that era. Later we watch a recreation of Yonezo stepping through Canadian customs, building a house in the woods, creating and tending a strawberry farm, and, when things take a terrible turn, getting relocated to an internment camp during World War II.

Drizzles of interactivity attached to most environments present another form of engagement. We take a photograph with a wind-up camera in Hiroshima, for instance, present a passport to Canadian authorities, and place stones into a wheelbarrow at the strawberry farm. These moments are short and simple.

Between these time and place-specific mini settings, which feel like theatre small sets erected before us, Randall reappears, visually and verbally—a combination of narrator, stage hand and tour guide. He reminds us that we’re observing artistic impressions of the past, “real” only in terms of emotion, beautiful in their imperfection, and constructed with a wonderful spatiality. At one point he says “careful, just take a step back” and then we see him before us, drawing a line of chalk across the ground, describing the environment we’re about to see as “an idea” and “an act of imagination.”

Randall frames the experience with warmth and intimacy, but also a stagey kind of detachment, relegating us to the role of observer and witness. In many VR experiences that are about watching and experiencing rather than playing or interacting, we want to connect and interact with the characters around us; we want to engage with them. But not here. We understand this is not our story. At the same time we know we’re not merely viewers, and that this experience is nothing like watching a film. The crucial, underpinning sensation is that of sharing a space. Randall understands that in VR, as in real-life, stories belong to spaces, and spaces tell stories. That understanding is core to what makes this experience so moving.